By: Katharina Funk

“Biodiversity is a global public good.”– Marie Haga

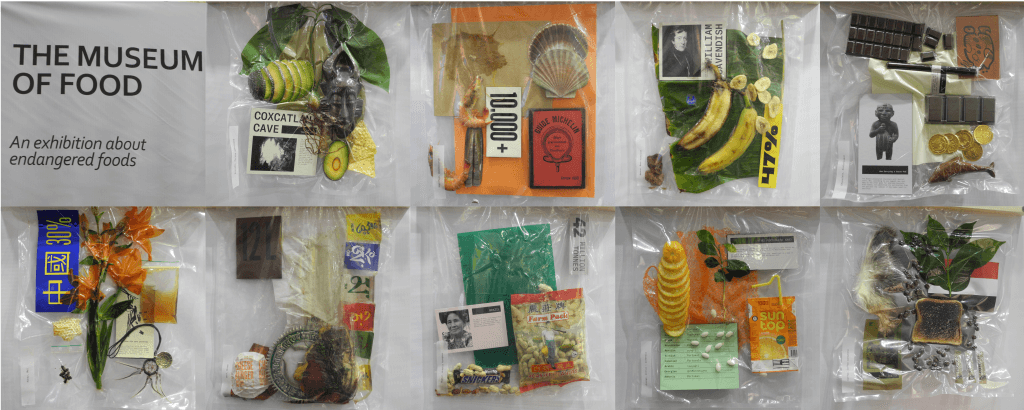

On the morning of the 9th of November there were strange plastic bags pinned on the wall of the Nordic Pavilion. They contained oranges, peanuts, bananas and, yes, chocolate. The bags represented nine time capsules, containing endangered food that will disappear in the foreseeable future due to climate change. It is a remarkable moment, realizing that we might not be able to eat chocolate in 15 years time, if we do not change our habits and make alternative choices. Other foods including honey, beef, shellfish, coffee and avocados will not be available in 2030, due to droughts, loss of biodiversity and the extinction of pollinators. So what can we do, what choices can we make, in order to save our food?

Every year we need to feed more people with less land and these intensive farming practices cause deforestation, soil exhaustion and water pollution. We are already experiencing a 70% – 80% decrease in insect lives due to our agricultural system and observe in general a massive biodiversity loss due to monocultures and land use change. There are 5500 varieties of crops that can be used for food, but only three of them make up 15% of our diet. An additional 75% of our calories consist of only another 12 crops and 5 animals.

But we are not only losing biodiversity, the variety within species vanishes as well. We used to have over 1000 different types of apples in Europe, today we consume only 6 of them. The US has lost 93% of their crops and animals since 1900. And China has only 10% of its rice variety from 1915. We are therefore losing genetic properties that might enable plants and animal to cope with future climate conditions, such as being drought resistant.

“We must save what we have because we don’t know what we need in the future. We only know we are losing options.” Marie Haga

But there is also hope: In Peru, for example, people are starting to find their way back to their own culture and food again and are very proud to see what a great variety of crops and fruits can be produced. In Lima the International Potato Center was established and people are now discovering what great variety of crops they have not been using for decades. Especially young people, who find job opportunities in gastronomy and try “new” old recipes, cause a booming export of Peruvian food. This valuing of products helps protecting biodiversity. And also Brazil, Sri Lanka, Kenia, Turkey and many more countries rediscover the value of the variety of fruits that have fallen completely out of their diets.

“If you go to a supermarket in Peru, you will find a least 20 varieties of potatoes, with different size, colour and taste.” Gycs Gordon

There is, however, always the need to increase the demand for different varieties of crops in order to make them accessible and establish them in the eating habits of people. Demand gives incentives for farmer to produce and sell various types of crops, so people can buy them for low prices on a daily basis. Therefore, there are many organizations, such as the Biodiversity for Food and Nutrition project, trying to use, for example, school feeding programs to raise the demand. In some areas mobile markets were established that can come to the areas where the more disadvantaged people are living and provide affordable, subsidised food.

“Change the image from poor people’s food to a gastronomic pleasure.” Ann Tutwiler

There is still a long way to go. We need to ask more from our food system than only calories. We need it to be sustainable, climate friendly, healthy and nutritious. We need it to support biodiversity and provide long term solutions. We must prepare to live in a warmer world. Maybe then there will be a change that we still might be able to eat chocolate and avocados in 2030.

This article is a resume of the discussion “Eat what’s worth saving” within the Food Day at the Nordic pavilion. Participants where: Marie Haga, Executive Director, Crop Trust; Ann Tutwiler, Director general, Biodiversity international; Erin Biehl, Senior Program Coordinator, Food System Sustainability and Public Health Program, Johns Hopkins Center for a Liveable Future; Gycs Gordon, Director, Commercial Office of Peru, Hamburg; Sudhvir Singh, Director of Policy, EAT Foundation; The session was moderated by Dan Saladino, Journalist and Producer, BBC, Food Program.