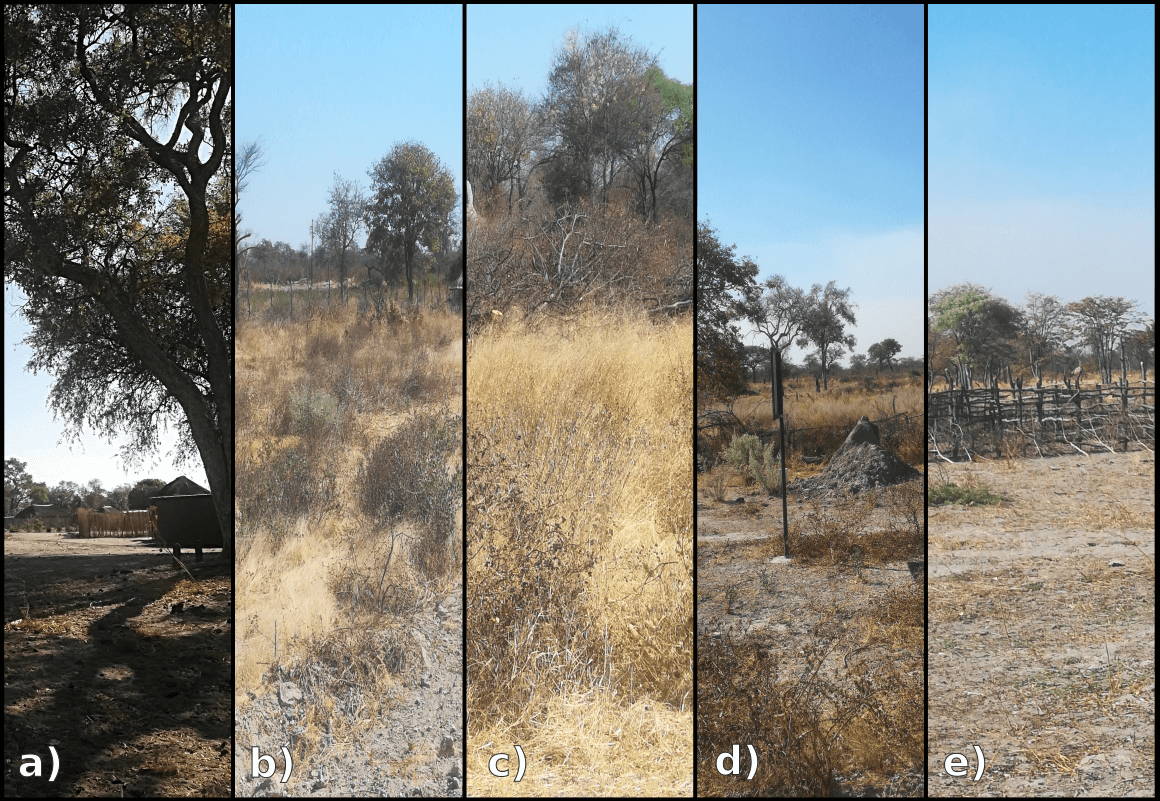

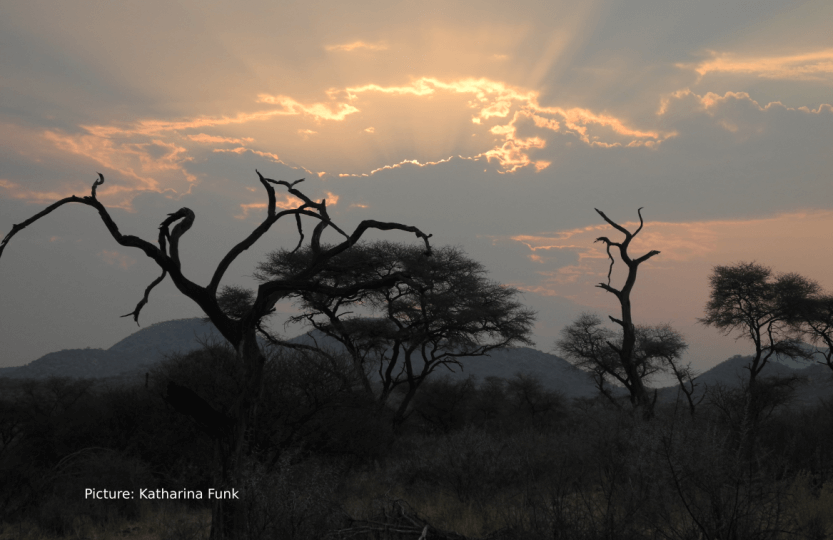

After two nights in the relatively clean and quiet Windhoek, I was looking forward to seeing the rest of the country. And lo! Suddenly, dusty Savannah as far as the eye can see. The dry grass was gleaming golden in the sunlight, many leafless and dried out bushes and trees were growing on each side of the road. Only on very few bushes I could spot the tender green of an approaching spring and occasionally I could see a tree in full blossom. Nevertheless, if one looked patiently out of the window of the car, one could get a glimpse of some animals in this desert-like landscape. Families of warthogs were playing alongside the road and behind the fences that where flanking the road, groups of baboons and antelopes appeared. Once, we saw two giraffes browsing on the leaves of an acacia tree and a female ostrich walked calmly along the road. There were also many birds and even though some looked familiar, I didn’t know their names.

But after kilometers and kilometers, the Savannah still looked the same, and even though I was straining my eyes, I couldn’t spot animals anymore. Trees, bushes, dry grass, sand, over and over again. For hours, nothing happened. I looked out of the window, into the monotonous landscape, trying to spot something that would stand out, something that would break the recurring scenery. But then there was again nothing, nothing except trees, bushes and dry grass, softly swaying in the wind. The journey seemed to stretch into infinity…

Around midday, we crossed the veterinary cordon fence (VCF), which runs through the whole width of Namibia, from East to West. Back in colonial times, it was meant for keeping the indigenous people in the North, and separating them from the, usually white, farmers in the South. Today, the fence (sometimes also called the “red line”) serves to control the transport of meat across the country. Since 1896, when a Rinderpest outbreak shook Namibia, it is not allowed to transport meat from the North to the South. In the 1960s, the fence was also used to isolate Foot-and-mouth disease outbreaks in the North from the farms in the South.

It is notable to contemplate the respective land tenure systems in Namibia differing between the North and the South: In the South, being influenced by German and South African colonial politics, and formerly occupied by German settlers, the land is owned by the farmers. Each farmer can buy land (5000 hectares in the North and Central Namibia, and even more in the South) and build up a commercial farm. (Check out our article about our stay at a commercial farm here.) As the land needs to be bought, it is freehold land. In the South, the most of the agricultural usable land belonged to commercial farms. We saw the fences, stretching for kilometers next to the road. In the North, most of the land is communal land, and everyone in the respective community is allowed to use it. Livestock is usually not restricted by fences and roams freely, often accompanied by a shepherd, guarding the cattle from wild animals. Some people have inheritance rights to use a certain piece of land but they cannot sell the land. Otherwise, the distribution and use of the land is in the sovereignty of the local chief. He (or she) can assign or withdraw land use rights. This, however, clashes with the concept of the management of a conservancy. Here, the deputies of the conservancy (as representatives of the government) can decide how the communal land is used and can declare certain land use zones, which can lead to local conflicts over land use rights. But often, this is well managed in conservancies and the chief acknowledges the land use zones and assigns land use right accordingly.

When we crossed the fence, our Professor said: “Now we are driving into the real Africa.” And lo! The scenery was changing: The fences next to the road vanished, and small villages with round huts made from clay or corrugated iron appeared. We could see children playing under Acacia trees and people walking along the road, carrying huge baskets on their head. Sometimes, some cows or goats where crossing the road, jumping nervously when a car approached them. Not always in the right direction. Sometimes we would see people were riding donkeys or just sitting in the shade of a tree, waving merrily at us. Our Professor was right: Whether this is the real Africa or not – this was substantially different from what we had seen before.

Thanks for sharing this post,

is very helpful article.