Professor Karim-Aly Kassam is not a tall man. But when he enters the stage – in this case the stage is the room between a blackboard and a table in a muggy lecture room in the GEO building at the University of Bayreuth – he has all the attention of his audience. In a very calm voice he speaks about his research in the Pamir region in Central Asia.

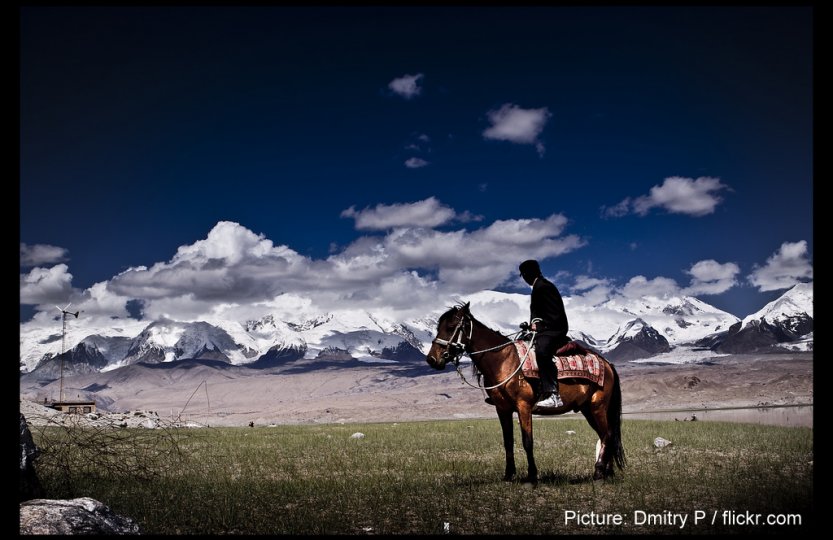

The Pamir mountains are a mountain range at the junction of the Himalayas and therefore a part of the area is also known as the “roof of the world”. Even though the biggest part is located in Tajikistan, they also cover parts of other Central Asian countries such as Kyrgystan, the Hindukush mountains in North Eastern Afghanistan, and parts of China.

Kassam, teaching at the Cornell University, takes the audience to a journey, a scientific journey. He talks about the genesis of a research program: first the idea, then the obstacles before and during the research and in the end the results. Coming from a cultural-social background, he wanted to have a closer look on the impacts of climate change on the life of indigenous people. To be more exact, his research in the Pamir region focussed on so called “ecological calendars”. Therefore, the name of the project happened to be “Ecological Calendars and Climate Change Adaptation in Central Asia”.

These calendars have been developed by the time of the year, the seasons, the weather and climatic conditions, mostly over the course of hundreds and thousands of years. In our “western” system, calendars depend on months, weeks, days, minutes – whereas in the Pamir region, nature is the main component of the calendars. The people of the Pamir, farmers and herders, don’t seed their plants on a certain day as people in our society use to. Professor Kassam and his research team spoke with the people of the Pamir, who gave similar answers in different regions : certain natural phenomena such as hearing the voice of a particular bird for the first time in the year, discovering water streams resulting from the snow melting in spring, or the seeing the blossom of a certain plant are used as an indicator for the correct time for seeding. Because of these phenomena, calendars arise that are valid for the whole course of a year just as the “western” calendars – with the difference that they don’t refer to dates or days but only to natural events.

But what happens, if these phenomena don’t appear due to changing seasons? What, if climate change is changing the timing of the blossom in spring or the migration cycle of birds is changing due to altering weather or extreme events? This is one of the questions, Kassam wants to examine with his research. There is a big difference in the understanding of agriculture between European farmers for example and the farmers from the Pamir: While a farmer from France or Germany might sow his seeds in March even though the weather has been different than in the years before, a Pamir farmer might wait for the voice of the bird, the water streams or the blossom of trees, even though this might occur later or earlier in the year than normally. During a research project in the Pamirs about a decade ago, villagers from the region reported their observations of changing rainfall patterns and temperatures, higher melting rates of snow and glaciers and higher flooding events. These observations cause anxiety as these unprecedented changes are a threat to their survival which is based on subsistence farming.

Kassam and his team compared the answers of the different indigenous groups they talked to in the Pamir with the results of climatic field measurements done in the region, partly by Professor Cyrus Samimi from the University of Bayreuth. These measurements include, amongst others, the data collection of temperature, humidity, wind speed and direction, soil moisture and radiation as well as vegetation mapping to create a time-series analysis of life cycles.

Combining the findings of the measurements with the knowledge of the indigenous communities in the Pamirs, new systems and new partnerships could help the people of the Pamirs to understand and adapt to climate variability. This way they can secure the food production they rely on so heavily in this harsh and remote area of the planet. “We must succeed in this. We have to be in the A-Team, not in the B-Team. Failure is not an option”, says Karim-Aly Kassam.

“We wanted to have a transdisciplinary approach in this research topic”, he says with his calm voice, folding his hands in front of his chest. This is important in order to have results that are highlighting the impacts of climate change on the people of the Pamir, he emphasizes. He tells how impressing the work with the people of the Pamir was, how hospitable they are, how proud. He talks about trust as well: “For this research, in this very disturbed area, trust between the different involved groups was indispensable.” The professor of Environmental and Indigenous Studies in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell University states also that research is all about trust. “Trust is the beginning of transdisciplinarity”, he says, closing his talk with a little smile.

How nature creates a calendar?

I never thought about this topic