By: Katharina Funk

Bula! from the UN-Climate Conference in Bonn. Bula is Fijian for “life” and is most commonly used as a greeting, wishing one good health. In this article we want to present an overview of what the COP23 is about.

The UN-Climate Conference takes place from 6 – 17 November 2017 in Bonn under the Presidency of Fiji. It is the 23rd meeting of the Parties of the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) as well as the 13th meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP) and the second meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA). This year’s primary task is to discuss the implementation of the Paris Agreement of 2015, which should ultimately result in a so-called “Book of Rules” that is to be approved during the next COP24 in Katowice, Poland.

Alongside the official negotiations of the parties, there are also many side events and exhibitions taking place in the framework of the conference. Though these are only to be attended with an official registration, there are also possibilities for citizens to visit various event throughout the city.

[bg_collapse view=”link” color=”#117BB8″ icon=”arrow” expand_text=”Fiji in Germany?” collapse_text=”Fiji in Germany?”]

First questions first. Why is the Conference taking place in Bonn when it is under Fijian Presidency?

Formerly, the hosting procedure was such that the holder of the COP presidency was also hosting the conference. Last year, however, no country from the UN Group Asia that was slated to host the meeting of the parties was willing to take over presidency. To fill the vacancy, the Republic of Fiji was prepared to take on the chair of the Conference but could not host the conference for organisational reasons. Under these circumstances, the regulations of the UNFCCC require that the conference be hosted in Bonn, where the UN climate secretariat is located.

The Republic of Fiji is a small island state in the South Pacific and is already strongly affected by climate change. Sea level rise, the salination of soils, and hurricanes threaten the 890,000 inhabitants of Fiji, as well as residents of other small island states in the Pacific. Over the last several years, Fiji took over the leadership of climate action in this region and was the first nation to sign the Paris Agreement. As Fiji now holds Presidency of COP23, this current conference has a strong emphasis on the fate of small island states when facing climate change impacts.

[/bg_collapse]

[bg_collapse view=”link” color=”#117BB8″ icon=”arrow” expand_text=”Bula Zone and Bonn Zone” collapse_text=”Bula Zone and Bonn Zone”]

Why are there two zones and what is the difference?

The Climate Conference is divided into two zones: the Bula Zone and the Bonn Zone.

The negotiations and official meetings of the parties take place within the Bula Zone. This is likewise where the main plenary located. Allowed entrance in this zone is limited to delegates and official observers. This year, Global Change Ecology four observer spots; eight students and alumni (four per week) have the possibility to follow the negotiations in person. However, for some topics the meetings are only open to participants (observers are not allowed).

The Bonn Zone is another conference building some distance away from the Bula Zone. This is where the Side Events take place. A huge exhibition area for NGOs and other organisations is located within this zone, and there are additional pavilions representing many countries where information about the local culture and climate action can be found. For COP23, GCE has 15 additional spots for the Bonn Zone, meaning another 30 students are able to attend Side Events and have a look at the exhibitions and actions. In the Bonn Zone you can also find the GCE exhibition booth.

[/bg_collapse]

[bg_collapse view=”link” color=”#117BB8″ icon=”arrow” expand_text=”What to expect from COP23?” collapse_text=”What to expect from COP23?”]

Some of the most pressing issues that will be discussed during the negotiations

After the successful drawing up of the Paris Agreement, it is now time to decide how this agreement can be implemented. There are some topics that have to be decided, amongst others the rules for the implementation, the NDCs, the Talanoa Dialogue, and loss and damage financing.

Rules for Implementation

One of the most important agenda items is the setting of the rules for the implementation of the PA. This should result in a so-called “Book of Rules” that is to be approved during the next COP24 in Poland.

“A major issue will be on how to produce a negotiating text that is Party-driven and inclusive, balanced on all the elements, and reflects the positions of all Parties.”[1] The question of how to differentiate between developed and developing countries will also be heavily discussed.

NDCs

The purpose and interpretation of the NDCs will be another controversial item. Most of the parties focus mainly on the mitigation component of the NDCs, whereas the LMDC (Like Minded Group of Developing Countries), the African and the Arab Group believe the scope of the NDCs covers besides mitigation also adoption and means of implementation.

Another key point will be what kind of information parties should report back regarding their contributions. Many parties stress that mitigation efforts should be reported in CO2-eq (Carbon dioxide equivalents), so as to be fully quantifiable; others, such as the LMDC, believe that comparison is not the purpose for this kind of information.

Facilitative Dialogue 2018

In the Paris Agreement, parties have decided to “convene a facilitative dialogue among Parties in 2018 to take stock of the collective efforts of Parties”. This dialogue was organised by the Presidencies of COP22 and COP23. They provide an informal note in which they refer to the Facilitative Dialogue as “Talanoa Dialogue” and ensure that “the dialogue will be conducted in the spirit of the Pacific tradition of Talanoa” which is “a traditional approach used in Fiji and the Pacific to engage in an inclusive, participatory and transparent dialogue” with the purpose of sharing “stories, [to] build empathy and trust.”

This dialogue “will be structured around three general topics: where are we, where do we want to go, and how do we get there.”

Loss and damage

As the COP23 is the first COP to be hosted by a Small Island State, there is hope that this year will feature a greater focus on Small Island Developing States (SIDS) alongside other developing countries. As these states are already hit hard by climate change impacts, it is crucial to find ways to generate and provide finance for loss and damage. There are, however, prominent voices that fear that developed countries seek to delay a result-oriented debate about the providence of finance for developing countries.

[1] https://www.twnetwork.org/climate-change/what-expect-fiji-cop

[/bg_collapse]

[bg_collapse view=”link” color=”#117BB8″ icon=”arrow” expand_text=”NDCs and Fair Shares” collapse_text=”NDCs and Fair Shares”]

Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) are the pledged efforts of the participating nations to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. In contrast to other climate protection standards that are legally determined at a conference of the parties, every country can decide for itself how high its NDCs should be.

Countries are obligated to update and communicate their NDCs in 2020. Countries cannot, however, be punished if they fail to fulfil their commitments. Germany, for example, is likely failing to meet its climate targets for 2020, which is to reduce emissions by 40%. Experts estimate that – without any additional action – emissions can be reduced at most by 30%.

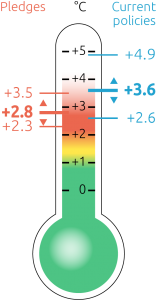

However, even if all countries would be able to meet their goal, there would be still a massive emissions gap (see also: “Critical Voices”), as the actual NDCs are not alone sufficient to meet the goal of staying well below 2°C. The NDCs are expected to be implemented from 2021 onwards; however, there is also a call for a bigger focus on pre-2020 actions, especially from the developing countries. These countries are concerned that developing areas won’t be able to meet even their existing obligations under the Kyoto protocol while shifting their focus to the time following 2020.

Fair Shares are the amount of contributions countries should pledge because of their global responsibility. These share depend upon historical responsibility (e.g. how much these countries have already emitted) and their capacity to act. Different countries must consequently act differently.

The issue remains that some countries, such as America and the EU, have a higher amount of Fair Shares than their total domestic decarbonisation. How can these nations fulfil their Fair Shares?

The solution could be to help other countries whose Fair Shares are still lower than their total decarbonisation. China, for example,still has a very low contribution to make, as it has not emitted a high quantity during past centuries. Because it is presently emitting massive amounts of CO2, it must be the duty of the other countries to fulfil their Fair Shares while assisting China with its decarbonisation.[1]

[1] For more information see: http://www.cidse.org/publications/climate-justice/equity-and-the-ambition-ratchet.html

[/bg_collapse]

[bg_collapse view=”link” color=”#117BB8″ icon=”arrow” expand_text=”America’s Withdrawal From the Paris Agreement” collapse_text=”America’s Withdrawal From the Paris Agreement”]

“The bottom line is that the Paris accord is very unfair at the highest level to the United States.” – President Donald Trump [1]

On June 1st 2017 US President Trump announced the United States’ intentions to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. Being the last state which has had not yet signed the Agreement, Syria affirmed its commitment for the Paris climate change accord on the second day of the Climate Conference in Bonn, leaving the US quite isolated in international climate change policy. However, according to the guidelines of the Paris Agreement, the US cannot exit the contract until November 2020. Until then, the US will continue to be party.

In a media note from August 4th 2017 the US State Department announced that it will continue to participate in the meetings in order to “to protect U.S. interests and ensure all future policy options remain open to the administration. Such participation will include ongoing negotiations related to guidance for implementing the PA.”

“This is”, says Meena Raman from the Third World Network, “like a marriage in which you have already announced that you’ll divorce in four years, but you still want to have a saying on how many children you want to have.”

There is, however, a countermovement. With the slogan “We are still in” many US citizens and representatives of US Cities and States have expressed their commitment to climate action and their disagreement with the official American policy direction. Prominent examples are the former mayor of New York, Michael Bloomberg, California Governor Jerry Brown, and his predecessor Arnold Schwarzenegger. As the official American Delegation was unwilling to set up a pavilion within the Bonn Zone, the U.S. Climate Action Center built an “unofficial” American pavilion between the Bula and the Bonn Zone. From this pavilion they inform about climate initiatives and actions in the US and assure the international community: We are still in.

[1] http://thehill.com/policy/energy-environment/335955-trump-pulls-us-out-of-paris-climate-deal

[/bg_collapse]

[bg_collapse view=”link” color=”#117BB8″ icon=”arrow” expand_text=”Sustainability of such an event?” collapse_text=”Sustainability of such an event?”]

Should climate scientists come together and cause large emissions to discuss about emission reduction?

As a huge event like a climate conference has a huge carbon footprint, it is necessary to take measures to ensure that COP23 is as sustainable as possible. As a voluntary commitment, COP23 aims to be EMAS (Eco Management and Audit System) certified. EMAS is an environmental management scheme based on EU regulations, requiring the use of renewable energies, waste management, and a general sustainable use of resources.

Waste:

In order to prevent the production of waste, the UNFCCC Secretariat and the German government utilize an electronic data transmission system and all exhibitors are urged not to distribute printed materials. Even though the sustainability guidelines are very clear, many exhibition booths still provide lots of flyers and printed material. There is, however, a strong effort made to enhance the distribution of electronic data. Waste bins encourage the separation of waste and every participant is given a drinking bottle that could be refilled at water dispensers located widely across the conference area. In addition, all temporary structures can be used again for future conferences.

Food:

UNFCCC claims that the food provided would be “mostly vegetarian”, with the aim to make at least 50% of the products regional and organic. Served meat are also always organic and fish is consistently certified. During lunch hours, there were usually three meals: one with fish, one with meat, one vegetarian. Even though this menu plan might be less meat than at former COPs, it certainly cannot be declared as “mostly vegetarian”.

Nature Conservation:

According to the COP23 webpage, no trees were felled in order to build the secondary structures; and, following COP23, the Bonn Zone “Rheinaue” area will be regreened using turf.

Mobility:

All participants were encouraged to offset their travelling CO2 emission (see also: “CO2 Offsetting”). Free bicycles were provided throughout the conference and electro shuttles could be used to commute between the Bula and Bonn Zones. Additionally, free local transport was provided for conference participants.

CO2 Offsetting:

Unavoidable CO2 emissions will be offset by supporting projects in Small Island Developing States. Institutions, organisations, and conference participants also have the possibility to offset their own carbon footprint with UNFCCC’s Climate Neutral Now initiative. [/bg_collapse]

[bg_collapse view=”link” color=”#117BB8″ icon=”arrow” expand_text=”Critical Voices” collapse_text=”Critical Voices”]

Perhaps the Paris Agreement is not as good as they want us to believe…

Though the Paris Agreement was broadly celebrated as a groundbreaking milestone in international climate negotiations, there are still many elements worthy of serious criticism. Many critical voices could be heard during this COP, inside the Bula Zone, in the Bonn Zone side events, and outside during the many demonstrations.

Emission Gap

One of the biggest issues is featured centrally in the latest “Emissions Gap Report” by the United Nations Environment Programme. It shows that the currently stated NDC’s cover approximately only one third of the emission reduction needed to reach the goal of staying well below 2°C. That means that even if every country fulfils its pledge, we will head into a world with 3°C of heating or more. If this emission gap is not closed before 2030, it is extremely unlikely that we can stay well below 2°C.

Private Business and Lobbyism

Another criticism often raised is that of lobbyism. NGOs claim that many politicians are connected with oil, gas, and/or coal concerns. The Netherlands’ Minister for Finance has worked for Shell in Berlin, Hamburg, and Rotterdam. Norway plays a significant role in the negotiations but continues its offshore drilling. Germany promotes itself as a forerunner in climate politics but still uses coal for energy production and will most certainly not meet its emission targets by 2020. Many claim that the “big polluters” need to be kicked out before there can be efficient, climate-friendly negotiations.

Slow Process

The negotiations around the Paris Agreement are very slowly progressing. This can be very frustrating, especially as the time to effectively tackle climate change is extremely limited. However,it is consistently challenging to have meaningful discussions with so many stakeholders and differing interests. As there is traditionally a decision at the beginning of the COP that every decision must be taken by consensus, there must be many compromises made, much goodwill shown. To return to the marriage analogy: The Paris Agreement was like the marriage itself. Everyone was euphoric. Now we find ourselves two years into this marriage and the enthusiasm has faded away. Sometimes it is necessary to let go of a bit of the “you” to be able to work on the “we”.

Missing Topics

There is also criticism by various parties that some important issues are not featured in the Paris Agreement. Likewise, certain topics are included but are not discussed and/or implicated. Amongst others, specific climate actions, slowing ongoing disasters, intergenerational equity, mentally disabled people, and the option of a radical reorganisation of our capitalism dominated system are left largely unaddressed. [/bg_collapse]

[bg_collapse view=”link” color=”#117BB8″ icon=”arrow” expand_text=”Outlook” collapse_text=”Outlook”]

What comes next…

Admittedly, COP has a lot of standing issues that must be solved–and solved soon. And yet, it is the best option we have at present, and there is little to indicate that there will be a better option within the next few years (if it is even possible to create something better in that dimension). We have to hope, therefore, that the parties are ready to deal with the climate impacts in an efficient and committed way.

We will see during the next week how much the Parties can accomplish, how many concrete actions for the implementation can be defined. Until then, it is our duty to express our own commitment–and our unwillingness to live in a 2°C warmer world. [/bg_collapse]

[bg_collapse view=”link” color=”#117BB8″ icon=”arrow” expand_text=”Further reading” collapse_text=”Further reading”]

Official COP23 website:

https://www.cop23.de/

Excellent overview on what to expect at COP23:

https://www.twnetwork.org/climate-change/what-expect-fiji-cop

Analyses the NDCs of countries and much more:

http://climateactiontracker.org/

Our personal wrap-ups of week 1:

[/bg_collapse]

1 Comment