On our second day in Windhoek and after a nice long sleep (shivering as the African sun still did not hold its promises), we tried out our rented car and headed to the GIZ (German Corporation for International Cooperation) office in Windhoek. It took some time to get used to drive on the “wrong” side of the road, but after a while it felt quite normal to drive on the left-hand side. The GIZ office can be found in a neat, white house, not so different from the family homes in the neighbourhood, surrounded by a huge wall, topped with barbed wire, and a nice blooming tree reaching over it, covering the street with faded-red blossoms. While the wall might seem unusual for someone from Germany, this is a common sight in Windhoek. Also gated communities can be seen often, and many houses are protected by a huge fence. We passed a sleepy guard and stepped into the building. Inside, it looked like a normal office which you could find all over the world, with posters on the wall and pictures from projects in Namibia. We were asked into a kind of conference room, with a long table and a beamer in the front. Sitting down, I could see long-tailed birds fluttering around the trees outside.

We met three GIZ employees, Johannes Laufs, who works on a project about bush encroachment, Innocent Haingura, who gave us insights how the GIZ supports CBNRM (community-based natural resource management) projects and Alexander Schönig who talked about the adaption of agriculture to climate change.

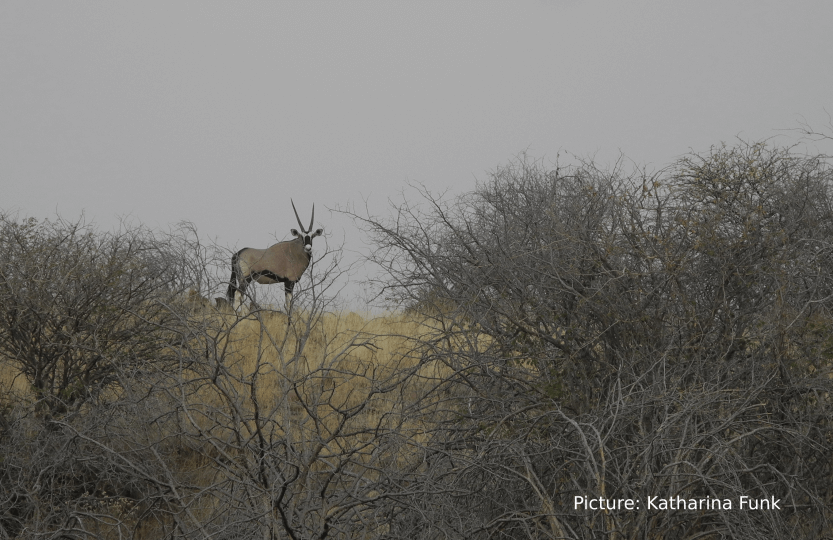

Johannes Laufs, a brown-haired man, who looked very German and behaved accordingly, told us about the issue of bush encroachment, which is a huge problem in Namibia. Approximately 30-45 million ha are affected – an area as big as Germany. Bush encroachment affects the savannah, an ecosystem that is usually composed of grass and occasionally by trees, because more and more bushes are growing there. This is mainly caused by overgrazing, the lack of natural fires (often because fires are suppressed by farmers) and according to some sources also the rising levels of CO2. And even though most of the bush-species are indigenous to Namibia (and not invasive), the ecosystem savannah is still disturbed. This means for example that the habitat for certain species vanishes because of the bushes or the available food range has changed, which in turn can affect biodiversity and ecosystem services accordingly. Bushes have also deeper roots than grasses and are thus affecting the groundwater. This is decreases the quality of land negatively: The livestock carrying capacity of the land is reduced by two thirds which in turn causes a loss of 100 million € per year. As bush encroachment diminishes not only the functionality of the ecosystem but also the income of the farmer, it is crucial to restore the natural savannah to guarantee food security and fight poverty in Namibia, Johannes Laufs tells.

However, the bushes provide a huge amount of biomass, which can be used in many ways. In total, 500 million tons of biomass can be harvested in Namibia every year and used to produce coal or energy. In fact, a 20 MW power plant could be sustained from within a 50-kilometre radius over 20 years, and there is furthermore a great potential to export coal or other products. This means, there could be a win-win situation accomplished, which can create environmental as well as ecological benefits.

However, a key factor for establishing a win-win situation is the creation of value chains and helping the farmers to utilize those. The biomass can be used to produce charcoal, which is also exported to Germany, wood chips that can be used for cement production as well as for power generation; or even more advanced materials such as chip boards, fuels or biodegradable plastic. The GIZ is working with approaches like these, introducing modern technology and approaches which can support, for example, the Namibia Biomass Industry Group.

According to Laufs, there is still a long way to go. De-bushing is expensive and work intensive and it often has to be redone after some while. Huge investments have to be made. But there is also the possibility to generate a substantial net benefit of around 48 billion Namibian Dollar over the next 25 years, with bush control and biomass utilisation. And there is even more to it: De-Bushing will restore the former carrying capacity of the land, ecosystem services will increase, more water will be available. This can, in turn, increase food and water security and combat poverty. So – if you find coal from Namibia in a German supermarket, you can actually help to bring back the savannah to Namibia.