Context

The coronavirus pandemic has affected societies, governments and economies across the world. Due to the numerous restrictions put in place to deal with this health crisis, many businesses are struggling, and layoffs are unavoidable in some areas. These pandemic restrictions have led to a temporary decrease in carbon emissions which has unexpectedly caused some countries like Germany to reach their emission goals in 2020 [1]. Nevertheless, the reduction of emissions is just a snapshot and not a long-term trend, proved by countries like the UK that have seen a rapid increase in carbon emissions after the lockdown has been lifted [2]. Unfortunately, the drop in emissions caused by the pandemic will only result in a 0.01 °C decrease in temperatures – which is well within natural variability [3].

In the face of a global recession, governments used stimulus packages to support affected business sectors to maintain employment or create new jobs. Simultaneously, the pressing challenge of tackling climate is more relevant than ever with 2020 being among the hottest years ever recorded [4]. There was great demand from scientists to include environmental and climatic conditions in the stimulus packages seeing the pandemic as a green rebound chance. The considerable spending during the time of crisis will have long-term effects on the structure of economies.

In this brief report, green stimulus packages are explained and connections to the 2009 financial crisis, where a green rebound was under discussion already, are shown. Next, the current stimulus packages of the G20 countries – which account for roughly 75 % of global carbon emissions [5] – are analysed according to their greenness and effectiveness to mitigate climate change. In conclusion, we deliver recommendations which stimulus measures prove the highest chances for tackling both the coronavirus pandemic, the economic downturn caused hereby and climate change.

Financial Crisis Stimulus Packages 2009

During the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008-09, carbon emissions reduced sharply, but already by 2010, emissions reached a record level [6]. This increase could be explained by the fiscal measures governments worldwide implemented to stimulate economies, which were rather designed to revive the existing economies than considering the environmental consequences. Although the recession caused by COVID-19 differs from the GFC, as a broader range of sectors is currently affected, some lessons could be learned from the last efforts of recovery [7]. The knowledge gained over a decade ago should be used to design recovery packages with a green stimulus to prevent a negative environmental impact like the one in 2009. Especially as COVID-19 spending with more than USD12 trillion to date [7] outsizes the GFC measures, which comprised approximately USD3 trillion [8].

Analysing the green stimulus of GFC recovery packages, 17.1 % of G20 public spending was dedicated to the support of renewable energy, energy efficiency and pollution control [9]. Those measures mostly focused on reducing carbon emissions while nature and biodiversity have been particularly neglected. One crucial finding emerges regarding the timeframe of the measures. After the economy began recovering in 2010, there has been no green expenditure of comparable size in any country, which suggests that short term policies are not sufficient for structural transformation of economies.

Moreover, a comparison of the stimulus types implemented in different countries shows an advantage of targeted policies as supporting green R&D investment over spending on large-scale infrastructure projects. As the limited success of the GFC recovery packages reveals, public spending alone cannot build up a sustainable economy. For this reason, various authors highlight the importance of pricing carbon and environmental damages [9]. A more general lesson learnt from the GFC crisis is that proper policy design is necessary to prevent environmentally harmful rebound effects [10].

Current Stimulus Packages

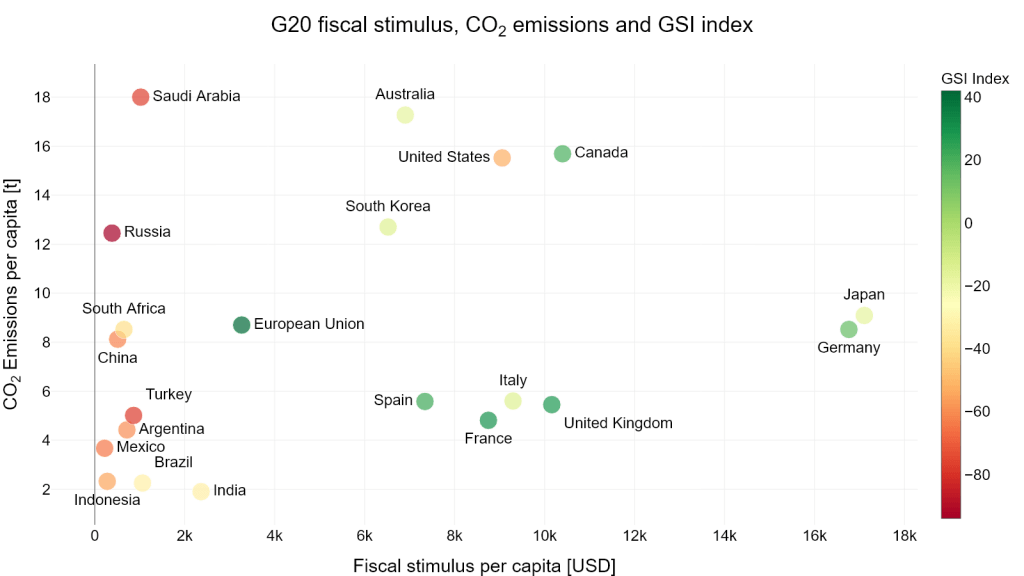

The amount of money spent by G20 governments on stimulus packages until December 2020 varies widely. Figure 1 shows per capita fiscal stimulus spending and per capita CO2 emissions. Furthermore, the GSI of those stimulus packages is displayed. Interestingly, most countries that spend little money on stimulus packages have a very low GSI index, indicating that sustainability and climate-friendly measures are not implemented. One reason could be that some of those countries still heavily depend on fossil energy sources like coal (China), natural gas (Russia) and crude oil (Saudi Arabia) and thus are not willing to engage in green recovery measures.

Source: Own graph (data: GSI & Stimulus [11], CO2 [12], Population [13])

Moving Forward

Due to the COVID-19 lockdowns, an 8% reduction of CO2 occurred. This reduction puts us within the 7.6% of global yearly reduction that the UNFCCC says are required between 2020 and 2030 to limit global temperature increases to 1.5°C – and achieve the Paris agreement [7]. Therefore, in the effort to mitigate anthropogenic climate change the fight against COVID-19 must be used as a turning point in the climate discussion [14]. As a result of the unprecedented year of 2020, we have seen that change is possible. This is our chance to move forward as the response to the COVID-19 pandemic has cast a light on many of the systemic issues long ignored while also showing some potential solution [15].

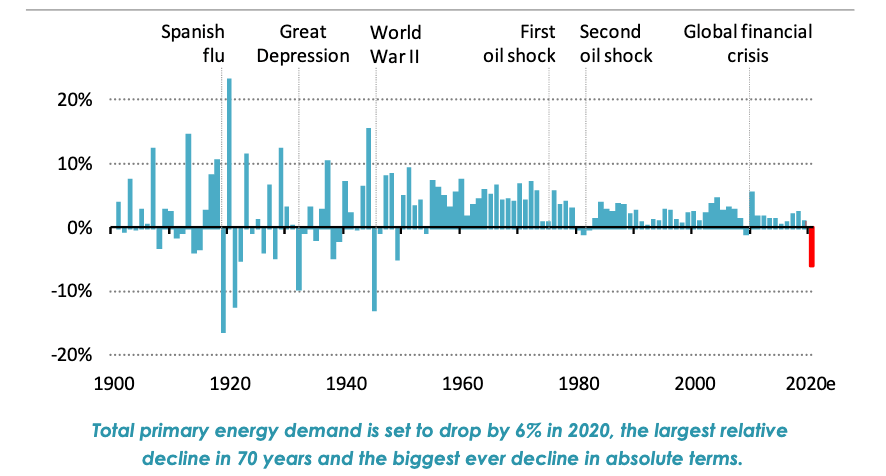

The effects of the pandemic are striking, in fact, global energy demand was estimated to decrease by 6% in 2020 which was not only seven times what was seen after the 2008-2009 economic crisis, but it was also the first major decrease seen since World War II (Figure 2) [14]. The pandemic effectively demonstrated that many of the “dirtier industries” and fossil fuels were not resilient in the pandemic, seeing large economic losses [14, 16]. As many experts argue, this weakening of the power of fossil fuels and changes in norm creates the perfect time to transition away for these industries [3, 14, 15, 16]. This change is enabled further by the USD 9 trillion pledged by governments to combat the economic situation – which on average accounted for 7% of a countries GDP [17]. Experts argue that if used effectively these packages can bring us out of the pandemic and minimize the effects of climate change at the same time [16]. This is the case because the stimuli have more lasting impacts than regular discretionary spending [14].

Seeing these recovery packages as a tool to fight anthropogenic climate change is essential because of their potential to lock us into a more sustainable renewable energy-based future rather than continue reinforcing the statuesque [18]. For packages to be effective at dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic and being climate-friendly, the International Energy Agency put forward some recommendations [5]. It provided a sustainable recovery plan to implement in the next 3 years (2021-2023). If implemented the annual energy related GHG emissions would be 4.5 billion tones lower in 2023 making 2019 the peak of global emission and would put us on the path of reaching Paris targets while also creating 1.1% of economic growth globally each year while creating 9 million jobs. The areas they recommended to focus investments in were: increasing energy efficiency of buildings and manufacturing, fostering low carbon electricity and transportation, and innovation. Therefore, creating jobs, increases in economic growth and a better future are all compatible and not at odds.

Conclusion

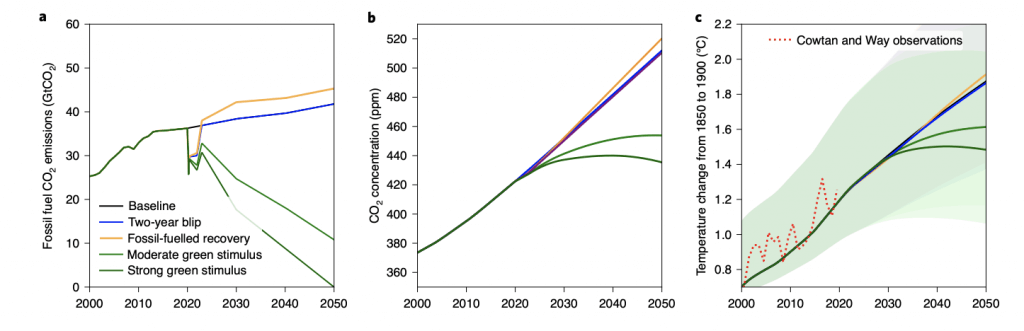

Moving forward, we are essentially at a crossroads of what to do, we can pick one of several emission scenarios as seen in Figure 3. Where we can recover with green stimuli, fossil fuels, or have a 2-year blip due to COVID-19 restrictions and then a return to normal [5]. These scenarios have very different implications for the future of the planet. Since governments are already investing so heavily into their economies now is the perfect time to lock in a more resilient and sustainable future, one that creates new jobs and opportunities, rather than repeat the mistakes of the past. In effect, as we fight to “get back to normal” it is essential to ask what normal do we want?

References

[1] DW (2021). Deutschland übertrifft wegen Corona Klimaziel 2020. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/de/deutschland-%C3%BCbertrifft-wegen-corona-klimaziel-2020/a-56121979 (last visited: 06.01.2021)

[2] Harvey, F. (2020). Surprisingly rapid rebound in carbon emissions post-lockdown. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jun/11/carbon-emissions-in-surprisingly-rapid-surge-postlockdown (last visited: 06.01.2021)

[3] Forster, P. M., Forster, H. I., Evans, M. J., Gidden, M. J., Jones, C. D., Keller, C. A., … & Turnock, S. T. (2020). Current and future global climate impacts resulting from COVID-19. Nature Climate Change, 10(10), 913-919.

[4] Yulsman, T. (2020). Has 2020 Ended as the Warmest Year on Record?. Discover Magazine. https://www.discovermagazine.com/environment/will-2020-end-as-the-warmest-year-on-record (last visited: 06.01.2021)

[5] Godinho, C. et al. (2020). The Climate Transparency Report 2020. Climate Transparency. https://www.climate-transparency.org/g20-climate-performance/the-climate-transparency-report-2020 (last visited: 05.01.2021)

[6] Cassim, Z. et al. (2020). The $10 trillion rescue: How governments can deliver impact. McKinsey&Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/the-10-trillion-dollar-rescue-how-governments-can-deliver-impact# (last visited: 17.01.2021)

[7] Hepburn, C. et al. (2020). Will COVID-19 fiscal recovery packages accelerate or retard progress on climate change?. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 36(S1).

[8] Robins, N. et al. (2009). A Climate for Recovery. The colour of stimulus goes green. HSBC Bank plc. https://www.globaldashboard.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/HSBC_Green_New_Deal.pdf (last visited: 17.01.2021)

[9] Barbier, E. B. (2020). Greening the Post-Pandemic Recovery in the G20. Environmental and Resource Economics, 76:685-703.

[10] Agrawala, S., D. Dussaux and N. Monti (2020), “What policies for greening the crisis response and economic recovery?: Lessons learned from past green stimulus measures and implications for the COVID-19 crisis”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 164, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c50f186f-en

[11] Vivid Economics (2020). Greenness of Stimulus Index. An assessment of COVID-19 stimulus by G20 countries and other major economies in relation to climate action and biodiversity goals. https://www.vivideconomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/201214-GSI-report_December-release.pdf (last visited: 17.01.2021)

[12] Crippa, M., Guizzardi, D., Muntean, M., Schaaf, E., Solazzo, E., Monforti-Ferrario, F., Olivier, J.G.J., Vignati, E., Fossil CO2 emissions of all world countries – 2020 Report, EUR 30358 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2020, ISBN 978-92-76-21515-8, doi:10.2760/143674, JRC121460.

[13] United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Populations Prospects 2019. Total Population – Both Sexes. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/ (last visited: 13.01.2021)

[14] Mukanjari, S., & Sterner, T. (2020). Charting a “green path” for recovery from COVID-19. Environmental and Resource Economics, 76(4), 825-853.

[15] Benach, J. (2020). We Must Take Advantage of This Pandemic to Make a Radical Social Change: The Coronavirus as a Global Health, Inequality, and Eco-Social Problem. International Journal of Health Services, 0020731420946594.

[16] IEA (2020), Renewables 2020, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2020 (Last visited 11.01.2021)

[17] IEA (2020), Sustainable Recovery, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/sustainable-recovery(Last visited 13.01.2021)

[18] Jagers S.C., Harring, N., Lofgren, A. et al. 2020. On the preconditions for large-scale collective action. Journal of the Human Environment 49(2):1282-1296

[19] G20 (2021). https://www.g20.org/en/index.html (last visited: 17.01.2021)