Education is the foundation upon which a prosperous and well-functioning society is built. On an individual basis, a quality education allows a person to cultivate the knowledge, skills, and values necessary to be engaged, productive, and self-governing citizens. This translates to enhanced socioeconomic status and empowerment, as well as reduced poverty and crime [1, 2, 3]. Education promotes health and well-being, equality, and responsible living [4, 5]. These benefits scale up: a society made up of educated individuals will tend to enjoy greater social and economic security overall. Considering that investment in education pays off for both individuals and society, why are there millions of people lacking access? Why are over 200 million children out of school and 750 million adults illiterate [6]?

In this context comes the Sustainable Development Goal 4, which aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”. In line with the goal, the UN looks to provide inclusive, free, and high-quality pre-primary, primary, and secondary education to all by 2030. Similar support should be provided for technical, vocational, and tertiary education. A focus lies in eliminating discrimination and giving equal opportunity to all genders, people with disabilities, indigenous peoples, and those in vulnerable situations. With this, the hope is to increase literacy and numeracy, raise the number of people with relevant skills for employment, and promote sustainable development [4].

Some progress towards SDG 4 has been made. For example, the proportion of young students out of school fell from 26% in 2000 to 17% in 2018 [6]. This achievement is partly due to the contribution of SDG Good Practices. This refers to significant initiatives, solutions, and success stories that show positive and scalable results for people around the world [7]. One example is the Fit For School Programme, which supports stakeholders in the education sector to implement WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) facilities and practices in schools. Taking these steps to maintain the conditions of the school and the health of the students not only improves their lives but also enhances learning outcomes.

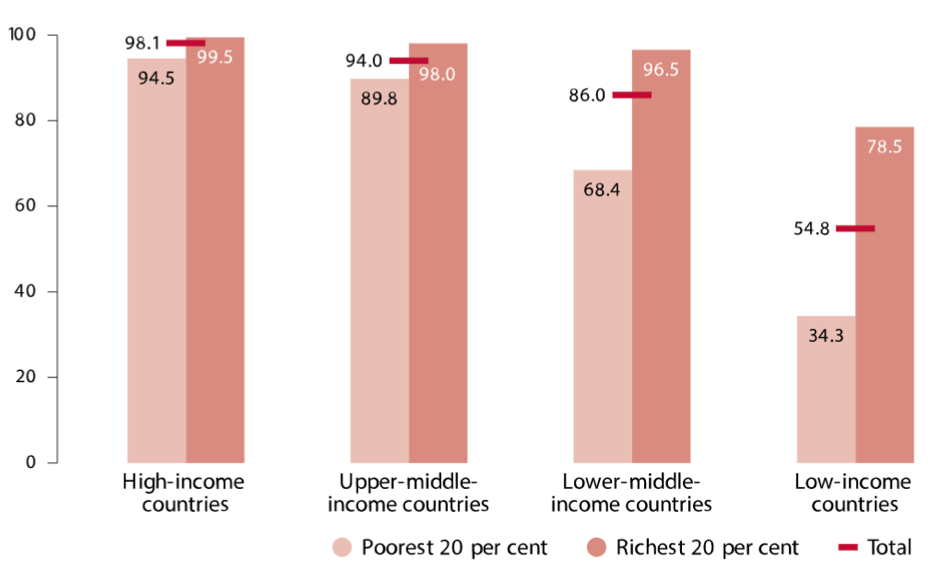

However, progress in SDG 4 is not coming fast enough – projections estimate that education targets will not be met by 2030 [6, 8]. A major problem is that access to education is not evenly distributed among all: vulnerable groups face many more barriers to education. For example, low-income countries show lower primary school completion rates relative to middle- or high- income countries (Figure 1). In lower income countries, the difference in education completion between the rich and poor is also greater. Furthermore, women and girls, as well as people with disabilities, have higher rates of illiteracy and school-leaving, particularly in lower-income countries and disadvantaged communities [6, 8]. This situation has only gotten worse with the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2020, the spread of COVID-19 prompted school closures in more than 190 countries across the globe. This means that 90% of students (1.57 billion people!) were not in school at some point during the pandemic [6]. Some schools turned to remote learning during this time, though this option was not available to 500 million or more students [8]. In this respect, a socioeconomic division is also clear. For example, in 2019 only 18% of households in Africa had access to the internet (and 11% owned a computer). In contrast, 87% of European households had access the internet in the same year (and 78% owned a computer) [8]. Without these tools, distance learning is severely limited. Additionally, while physical absence impacts learning outcomes directly, it does go further. For many children, school is where they can have a meal, gain access to health services, and escape violence [8, 9]. Losing access to school thus has far-reaching impacts on the fundamental well-being of students, particularly those that are already disadvantaged.

However, in the end, the pandemic has simply exacerbated existing infrastructure problems, income inequality, and gender and disability issues that already hindered our ability to provide education to all. It is now time for us to step up to the plate and address both short-term and long-term barriers through the recovery process by “building back better” [10]. In this context, UNESCO has launched a multi-level response to protect the right to education by uniting actors, providing resources, and giving technical assistance [6]. UNICEF has also scaled up their support for education recovery [6, 9]. By supporting cooperation like this, learning from and implementing Good Practices, and prioritizing education for all, we can avoid worsening a generational catastrophe!

References

[1] Kim SW, Cho H, Kim LY. 2019. Socioeconomic Status and Academic Outcomes in Developing Countries: A Meta-Analysis. Review of Research in Education 89(6).

[2] International Center for Research on Women. 2005. A second look at the role education plays in women’s empowerment.

[3] Hjalmarsson R and Lochner L. 2012. The impact of education on crime: international evidence. CESifo DICE Report 2/2012.

[4] Hahn RA and Truman BI. 2015. Education Improves Public Health and Promotes Health Equity. International journal of health services: planning, administration, evaluation 45(4).

[5] SDG-Education 2030 Steering Committee Secretariat.Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4).

[6] United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals: Quality Education.

[7] UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2020. SDG Good Practices: A compilation of success stories and lessons learned in SDG implementation.

[8] UN Statistics Division. 2021. SDG 4 Quality Education.

[9] UNICEF. 2021. COVID-19: Missing More Than a Classroom The impact of school closures on children’s nutrition.

[10] World Bank Group. 2020. Building back better: education systems for resilience, equity, and quality in the age of COVID-19.