Imagine a major port city suddenly finding itself without a river. This is not a hypothetical scenario from a dystopian novel; it is the unfolding reality in Leticia, Colombia, where the river is no longer a given, but is becoming a memory.

For decades, the Amazon River has defined the life, economy, and borders of the “Triple Frontier” (Colombia, Brazil, Peru). However, new hydrological measurements reveal a geomorphological shift: the Amazon’s main channel is actively migrating south, leaving the Colombian bank high and dry.

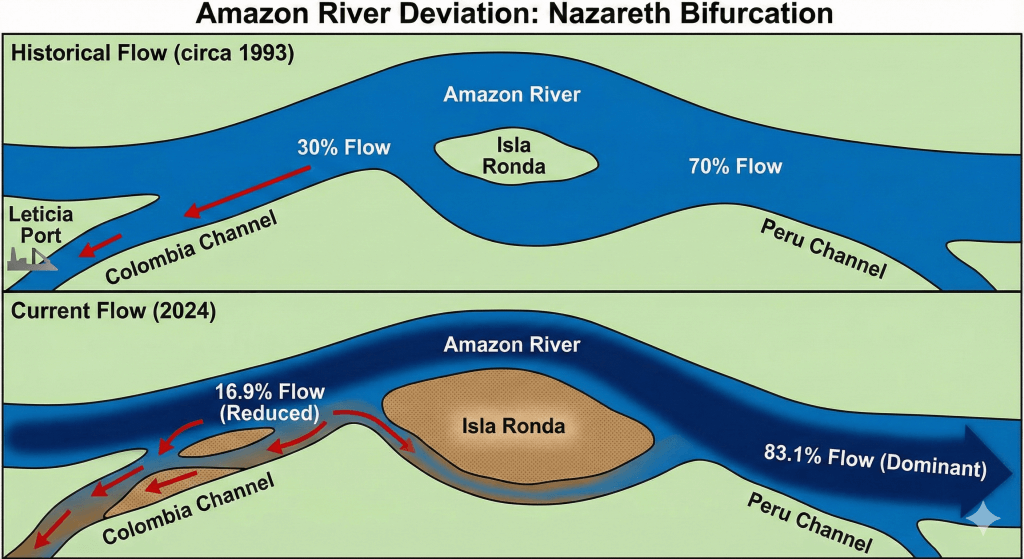

According to recent data from the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (UNAL), the deviation is no longer a slow geological process—it is an accelerated crisis. What before was a 30 %, today is only 16.9% of the Amazon River’s water flows through the Colombian channel, while the vast majority (over 83%) has diverted toward the Peruvian coast.

This is not just a story of climate change. It is a story of 20 years of overlooked science and a sudden diplomatic crisis over a new island that has literally redrawn the map: Isla Santa Rosa.

Why is it happening? A Tale of Three Islands

To understand why this city is losing its access to the Amazon, we must look at three specific geological formations that are acting as the architects of this tragedy.

- Isla Ronda (The Diverter): Upstream at the Nazareth Bifurcation, this massive island is the root cause. It has grown to a point where it is physically pushing the river’s main current into the southern (Peruvian) channel.

- Isla de la Fantasía (The Wall): Located directly in front of Leticia’s port, this sediment trap has stabilized into a permanent barrier, blocking the city from the river and turning the harbor into a stagnant backwater.

- Isla Santa Rosa (The Dispute): This is the new geopolitical dilemma. A massive formation that emerged in the river, it is now the center of a diplomatic difference between Colombia and Peru. While Colombia historically accessed the river here, the shifting channel has led Peru to claim jurisdiction over the island, increasing the isolation of Leticia.

The result is that the “port” of Leticia is increasingly becoming a stagnant backwater lagoon, accessible only by small boats during high water and completely cut off during the dry season.

The Accelerator: Climate Change and the Super-Droughts

While river meandering is a natural process, the speed of this shift is intensified by the global climate crisis. The historic droughts of 2023 and 2024, driven by intense El Niño events and Atlantic warming, lowered river levels to record minimums.

During these low-water periods, the weak current in the Colombian channel lost the hydraulic power needed to “flush” out the sediment. Sandbars that usually wash away in the rainy season have instead calcified and vegetated, turning temporary obstacles into permanent landmasses.

Implications: Beyond the Water Line

The deviation of the Amazon is not merely a logistical inconvenience; it is a systemic shock to the region’s hydrology and biology.

1. Ecological Collapse of Wetlands (The Yahuarcaca System)

The most urgent ecological threat is to the Yahuarcaca Lakes, a complex wetland system just upstream from Leticia. These lakes are not fed by rain, but by the “pulse” of the Amazon River, which recharges them via underground channels and seasonal overflow.

- The Risk: As the main channel moves to Peru, the hydraulic pressure required to fill these lakes diminishes, affecting the primary production for the local ecosystem and serving as a model for how floodplain lakes sustain the wider basin.

- The Impact: If these lakes disconnect permanently, the primary nursery for the region’s fish populations and the hunting grounds for the endemic Pink River Dolphin (Inia geoffrensis) is lost. For indigenous communities like the Tikuna and Cocama, this is not just an environmental loss; it is the erasure of their “amphibious culture” and food security.

2. The Geopolitical Dilemma (The Moving Talweg)

The border between Colombia and Peru was fixed by the 1922 Salomón-Lozano Treaty, based on the river’s Talweg—the line of deepest flow. But rivers are dynamic, and treaties are static.

- The Question: If the deep channel permanently shifts kilometers into Peruvian territory, does the border move with it? Or does Colombia retain sovereignty over a dry riverbed?

- The Flashpoint: The emergence of Isla Santa Rosa is a symptom of this ambiguity. Peru claims it is an island in their river; Colombia claims it is part of the historic channel. This geological confusion has now escalated into a diplomatic stalemate.

Conclusion: The Point of No Return?

The tragedy of Leticia is that this hydrological change was a chronicle of a shift foretold.

Since the early 2000s, researchers from the Universidad Nacional de Colombia warned that the Amazon was behaving as an anastomosing river—a multi-channel system prone to rapid switching. They prescribed specific engineering interventions, such as submerged spurs (espolones) and strategic dredging at the Nazareth Strait, to guide the flow back to Colombia.

Those plans were ignored. Now, the region faces an unavoidable choice between two difficult paths:

- The “Hard” Path (Geo-engineering): Attempting to reverse nature. This would require a massive, binational dredging operation and the construction of river training structures. However, the “tipping point” may have already been reached, where the sediment consolidation at Isla Ronda is so advanced that the river no longer has the energy to be redirected, making this an uphill battle.

- The “Soft” Path (Adaptation): Accepting that Leticia is no longer a river port. This implies a radical transformation of the city’s economy, shifting away from river commerce and potentially relocating the port facilities kilometers away to a point where the channel is stable—effectively acknowledging that the river has left.

Ultimately, the Amazon teaches a humbling lesson: water does not respect political borders or human infrastructure. Whether through immediate, high-cost engineering or painful adaptation, Colombia must act. If the sediments settle, Leticia will not just be a city without a river—it will be a monument to the cost of ignoring science.

References:

- Periódico UNAL (2024). “El río Amazonas se sigue desviando hacia Perú: nueva medición muestra que hoy Colombia solo tiene el 16,9 % de sus aguas.” Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

- El País (2025). “El problema ambiental que amenaza con dejar al puerto colombiano de Leticia sin conexión al río Amazonas.” El País América Colombia.

- InfoAmazonia (2025). “La advertencia científica de hace décadas sobre el río Amazonas y Leticia que fue ignorada.”InfoAmazonia.

- La Silla Vacía (2025). “Colombia se quedó atrasado en corregir la dinámica del río Amazonas.” La Silla Vacía.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2002). “Amazon River, Leticia – Image ISS004-E-12730.” NASA Gateway to Astronaut Photography.

- BBC Future (2025). “The photos showing why pink dolphins are the Amazon’s great thieves.” (Image Credit: Thomas Peschak).

- Historia y Región (2016). “La ocupación peruana de Puerto Leticia.” (Map Reference).

- Facebook Archive. “Historical Press Release on Amazon Deviation.” (Image Reference).

- Wikimedia Commons. “Map of the Salomon-Lozano Treaty.” (Public Domain).

I'm interested in the link between people and nature, specifically how that plays out in politics and electoral processes. I would like to understand how environmental choices shape elections and global policy (and vice versa) in an increasingly divided world.

This account highlights a stark and urgent transformation of Colombia’s Amazon frontier, where the river that once defined Leticia is slipping away due to accelerated geomorphological changes. Thank you for bringing attention to the complex interplay of natural processes and human oversight that now threatens both livelihoods and regional stability.

fantastic blog

nice topic