I bet you can recall at least one time you knew what was good for you yet chose otherwise. For me, it was smoking cigarettes for a decade. I even took a formal course on the benefits of tobacco cessation at the five-year point yet carried on smoking for another five years. The point I would like to make is that changing one’s behavior is not always as simple as knowing better, even when the choice is to prevent the looming mass extinction. I don’t want to suggest that choosing to consider or even adjust one’s ecological footprint is the same as choosing not to inhale one of the world’s most addictive, accessible and socially accepted substances. I do, however, want to emphasize that education is not necessarily the first answer to the long list of environmental challenges.

Yet education as a primary solution seems to come up a lot in university classrooms when discussing sustainability challenges. If people only knew what microplastics did in the ocean, they would choose reusable packaging and natural fibers; If people only knew the implications of buying conventional, non-organic produce, they would choose local and organic; If people only knew the unethical and environmentally degrading effects of the meat, eggs and cheese they love, they would change!

It’s not so simple. What changes behavior is much deeper than knowledge. Behavior change can be a complex equation of esteem, culture, support, prioritization and, particularly, access: choice is a prerequisite to change, and a lot of people don’t have access to an equivalent alternative, or REAL choice, in their lives (e.g. where they shop, what they eat, the clothes they wear, how they heat their homes).

Consider Maslow’s hierarchy: in order to self-actualize, a person’s basic needs for food, water, shelter, security and healthy social relationships need to first be satisfied. Then consider that a third of the global population doesn’t have access to a basic necessity: safe drinking water. And it’s estimated every 6th or 7th person on Earth has a mental or substance abuse disorder. That can make just getting through a day a challenge, let alone choosing to up your game in a collective effort to save the world as we know it. Truth is, a lot of people are struggling to meet their basic and mental needs, and unless reducing their ecological footprint is going to immediately provide relief, it may be unrealistic to expect them to change their ways even should they ‘know better.’

Beyond statistics and surveys, most of the people I know do have their basic needs met and are of relatively healthy mind. Yet, they are also too busy hustling at their jobs and/or raising their kids and/or managing their health to allocate even a little bandwidth to minimizing their ecological footprint or responding at all to what’s being called a global ecological collapse. If asked, (and I do ask), of course they care. Of course they would want to help…if it weren’t for their sick in-laws or unexpected car repair or low self-esteem remedied only by the short bursts of endorphins triggered when buying material things they know they don’t actually need—but which feel so good to buy.

People’s lives are inflated by a myriad of both externally and internally imposed demands that are seemingly more immediate than reducing their ecological footprint, despite their level of education. I value education and agree that education can be the first step in making positive changes, individually and as a community. I am also aware it is a privilege to have the opportunity to reflect on the ecological significance of my personal existence, and it is naive to believe that everyone else would too if only they knew.

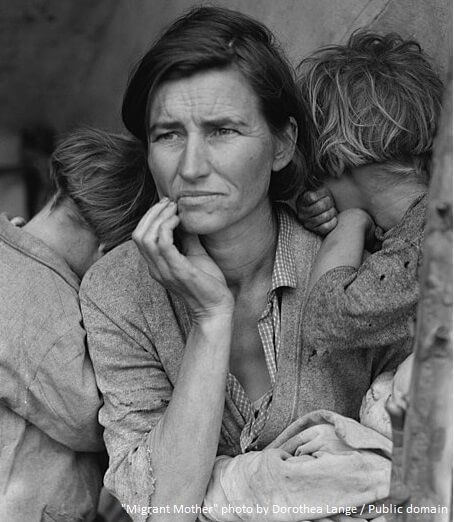

I do not mean to dismiss the meaningfulness of education altogether. There is one approach to education that studies show to be an essential component to building a sustainable future: the education of women, especially young girls. While being powerful agents of change, women around the world are oppressed by gender inequality, wage discrimination, sexual suppression, gender roles and gender violence. In 2012, there were 65 million girls denied education globally and today two-thirds of the 792 million illiterate adults in the world are women.[i] There are 32 million fewer girls are in primary school than boys.[ii] But evidence shows that women with increased access to education improve their personal health and well-being, that of their families and, by extension, their communities—well-being beyond physiological health, but also mental, social and environmental.

To break it down briefly, (because really this could be an entirely separate article), educated women have increased earning potential. According to the World Bank, for every extra year of primary education a girl receives, her wage increases an average of 10-20%. Women reinvest an average of 90% of their income directly back into their families, supporting their families’ health and well-being and, by extension, that of their local community.[iii] Educated women are more than twice as likely to send their children to school,[iv] and these educated children of educated mothers become educated citizens who are more inclined to show greater concern about the well-being of the environment, use water more efficiently, build and maintain renewable energy infrastructure, and recycle. More educated communities are more likely to make their neighborhoods safer, more sustainable, and more resilient. [v]

It can be helpful to understand things from a systems-thinking perspective, how different components of a system interact with each other. In doing so, we can identify leverage points within the system to maximize the impact of our effort (system inputs). So, as I wrote, people’s lives are inflated by a myriad of both externally and internally imposed demands that are seemingly more immediate than reducing their ecological footprint…However, when we focus on educating girls and women as an input to a complex global system, we leverage the investment of education by focusing on a group of people that, when educated, can directly ease many of these imposed demands, thus supporting enormous strides toward a sustainable future on multiple levels, including health, social justice and equality, economic, environmental, and the list goes on.

[i] EFA Global Monitoring Report

[ii] Education First: An Initiative of the United Nations Secretary General, 2012

[iii] United Nations Sustainable Development Report

[iv] UNICEF, 2010

[v] United Nations Sustainable Development Report

nice topic thanks