While nature preserves traces of past climates in ice cores, tree rings, and sediments, human records provide a unique and often overlooked perspective1. Diaries, harvest logs, ship logs2, art, and architecture can reveal how people experienced and responded to changing weather patterns over the course of centuries. These sources complement scientific data and provide context for how climate influenced societies, economies, and ecosystems.

Human records are also an important source of information for understanding past climates. What’s more, when climatologists and historians collaborate, they can open up a whole new field of research. For instance, historical maps and paintings can depict frozen rivers, glacier extent, and various plant species. Together, these sources paint a picture of what the climate was like in the past.

Humans as a climate witnesses:

While ice cores can provide insights into the climate of the last 800,000 years, historical data is limited to the period of human documentation. Nevertheless, it is important to gain a deeper understanding of the state of the Earth during our ancestors’ time. In Libya, for example, historians have found cave paintings of elephants, giraffes, and swimmers. These areas are deserts today, but the paintings show that the region wasn’t always so arid. A more humid climate favoring vegetation and water sources must have prevailed for people and animals to live there.

Figure 1: The deserts in northern Africa were once greener. Cave paintings from Libya often show animals that cannot survive there anymore.

Roberto D’Angelo (roberdan) – This image was originally posted to Flickr as DSCN3916

A study by Manning and Timpson (2014) supports this argument. The researchers analyzed over 1,000 bone, wood, charcoal, seed, and other plant and animal remains across the Sahara Desert. Using C14 analysis, they were able to date those findings. They located large clusters of human presence between 10,500 and 5,500 years before present (BP), indicating that the region was much more habitable at that time. This time span is known as the African Humid Period, when the Sahara was greener and had lakes and rivers.

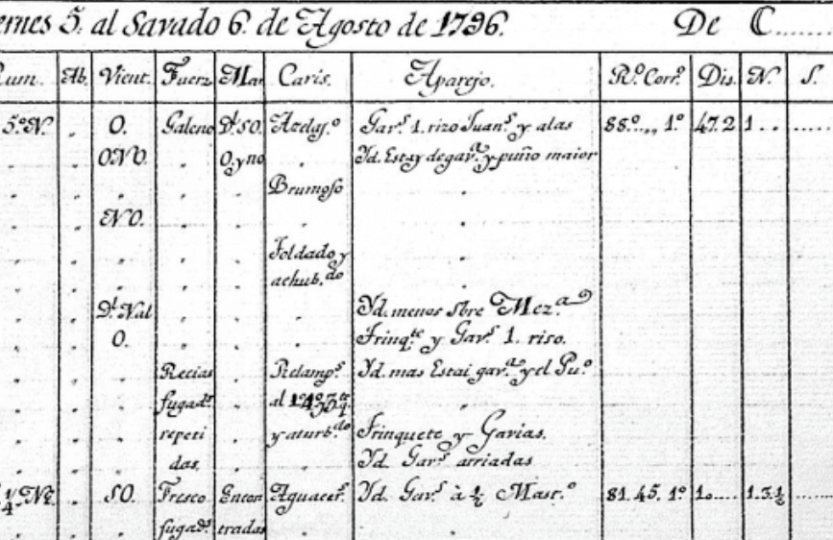

Historical data is rarely found in the form of cave drawings. Most of the available data comes from written records and documentation, which are mostly restricted to regions with a long tradition of writing, such as Europe and Asia. Written historical documentation can take the form of logbooks or harvest records. At best, logbooks are simple descriptions of weather and wind conditions, and harvest documentation often only describes spring and summer temperature anomalies. Therefore, historical data has some limitations, but when a large amount is compiled, it can complement natural climate proxies, allowing us to reconstruct climate fairly accurately.

Although historical records have limitations, such as regional bias and incomplete data, they are still valuable supplements to natural climate proxies. When carefully compiled and interpreted, these human-made sources enrich our understanding of past climates by offering insights into environmental conditions and how societies perceived and adapted to them. Science and history form a powerful partnership in tracing Earth’s climate journey.

- Disclaimer: This blog entry is the second part of the A Journey Through Time series ↩︎

- Image taken from: García-Herrera, R., García, R. R., Prieto, M. R., Hernández, E., Gimeno, L., & Díaz, H. F. (2003). The use of Spanish historical archives to reconstruct climate variability. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 84(8), 1025–1036. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-84-8-1025 ↩︎

I was born in Luxembourg and raised in the Müllerthal region. The region's fascinating natural landscapes sparked my interest in environmental sciences at an early age. This led me to study Geography in Innsbruck, where I specialized in physical geography and enjoyed the beauty of the Alps. After completing my B.Sc., I moved to Bayreuth to continue with a Master's in Environmental Geography, where I am particularly interested in the impacts of climate change on the environment and ecosystems.

Thanks for sharing such valuable information.